The Bear Case for Ginnie Mae Issuers

- Sep 22, 2022

- 8 min read

Updated: Sep 22, 2022

September 22, 2022 | Premium Service | A couple of years ago in The Institutional Risk Analyst, we predicted the impending collapse of the mortgage industry due to COVID. In “The Bear Case for Mortgage Lenders,” we described how the true risk to mortgage lenders is not insufficient capital but the cost of default servicing, when consumers cannot pay and the servicer is required to advance principal and interest payments to bond holders. But then the Fed rode to the rescue.

By May of 2020, the banking industry had put almost $70 billion aside for credit losses and mortgage lenders were preparing for Armageddon as millions of Americans were given loan forbearance. By the end of the year, however, even as COVID lockdowns started to seriously damage the global economy, the problem went away. By June 2020, the mortgage industry was in the midst of a boom caused by a 300bp decrease in lending rates thanks to the FOMC. The Fed's quantitative easing or QE made the problem of financing loan delinquency go away -- until now.

As lending volumes soared into Q4 of 2020, the vast surge of cash flows moving through custodial accounts floated the liquidity needed for funding COVID loan forbearance and essentially made bank warehouse and advance lines unnecessary. The chart below from the Mortgage Bankers Association shows actual and projected lending volumes for 1-4 family loans.

We wrote back in 2020:

“The extraordinary boom in the US residential mortgage market has pushed up volumes for new issuance of mortgage backed securities to over $440 billion per month through August. Even as commercial banks face years of uncertainty due to the credit cost of COVID and its aftermath, nonbank mortgage lenders are today's golden children for Wall Street – at least for now.”

In Q2-Q4 of 2020, the US mortgage industry originated over $1 trillion in residential mortgages. The profitability of this production was unprecedented, but now the FOMC’s QE bond purchases are at an end, mortgage rates are north of 6% and volumes are falling to 1/3 of 2021 levels. Taken together, the mortgage industry is headed for a serious crisis in 2023. Without the vast amounts of liquidity provided during the lending boom of 2020-21 c/o the Fed, and with loan delinquency rapidly rising, the mortgage sector and specifically government lenders appear to be in serious trouble.

Source: MBA, FDIC

One of the basic rules about the government loan market is that lenders are overpaid for selling government loans into Ginnie Mae mortgage-backed securities but then lose money servicing. During times of high loan delinquency, Ginnie Mae servicers can experience operating losses once the rate of past-due loans goes above 5-6%. The servicer must advance cash to cover P&I payments to Ginnie Mae bond holders and taxes and insurance (T&I) to protect the value of the house. Servicers are not fully reimbursed for expenses in the government loan market.

Kaul, Goodman, McCargo, and Hill (2018) wrote an excellent monograph on these costs for Urban Institute. “Servicing FHA Nonperforming Loans Costs Three Times More Than GSE Nonperforming Loans,” they found. This is why the FHA lenders receive 44bp for servicing vs. 25bp for conventional loans guaranteed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. But even the higher servicing fee for FHA loans does not cover all of the expense of servicing Ginnie Mae loan defaults. With default rates rising back to pre-COVID levels, most Ginnie Mae servicers are losing money and the tide of red ink is rising.

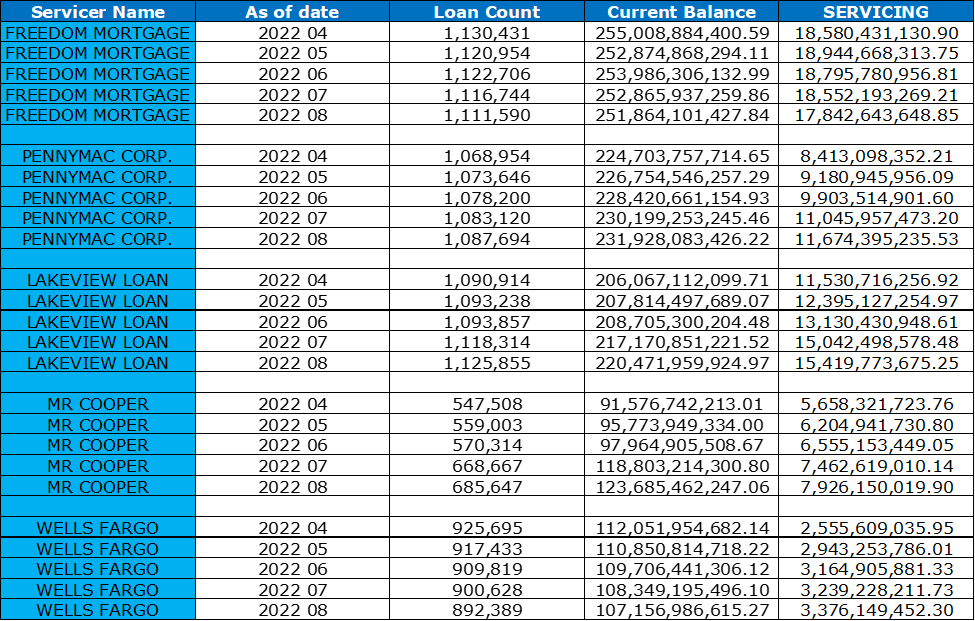

At the start of 2020, just prior to COVID, FHA delinquency was at 17% vs the current rate of 8.85% as of Q2 2022. Looking at the rate of growth in advance rates, which measure the amount of money being paid on behalf of delinquent borrowers, delinquency is rising. The table below shows some of the larger government seller/servicers in the government loan market. The column on the far right shows the level of advances made on behalf of defaulted borrowers through August.

Servicer Advances

What the table illustrates is that the amount of cash being advanced by large Ginnie Mae servicers has generally been increasing since April, an indication that reported levels of loan delinquency are likely to rise in the future. Of these top servicers, only Freedom Mortgage has been reducing advances as it resolves its backlog of early-buyouts or "EBOs" of defaulted government loans.

Data from Black Knight (BKI) reportedly suggests that re-default rates for loans modified during COVID forbearance are running at about 11 percent. But significantly, the BKI data excludes large Ginnie Mae issuers including PennyMac (PFSI), Freedom Mortgage, Mr. Cooper (COOP), and Carrington Mortgage. With these issuers included, we believe based upon anecdotal reports from servicers that the redefault rate is closer to 15-17%.

The risk for the future in the mortgage market is that higher levels of delinquency will force servicers into larger operating losses, especially in the government loan market. While the GSEs reimburse conventional issuers for expenses after four months, in the government market servicers must finance all loss mitigation activities until the loan is either re-pooled into a new MBS or goes to foreclosure. Ginnie Mae servicers tend to lose $5-10k per loan that goes to foreclosure, adding to the overall expenses.

With half a million people still in COVID loan forbearance, the actual delinquency rate for FHA loans is already above 10% and is growing fast. Home foreclosures are now underway after the end of COVID moratoria. As one veteran operator told The IRA last week:

“We may have reached a new normal for mortgage markets. It is characterized by forbearances settling in at around half a million mortgages and around 2 million delinquent mortgages, with foreclosure starts around 30,000 per month. Fortunately to date, most of the 8.9 million borrowers who took up forbearance during COVID have exited successfully.”

The wild card in the equation is the proposed issuer eligibility rule from Ginnie Mae, which we described in detail in National Mortgage News (“Government Lenders Await the McCargo Rule”). The prospect of lower leverage and thus profits for government lenders has drawn a negative response from warehouse lenders, who rightly view the Ginnie Mae action as hurting the credit standing of independent mortgage banks. The prospective rule from Ginnie Mae has also hurt liquidity for government mortgage servicing rights (MSRs), an ominous development as the industry heads into a period of low volumes and consolidation.

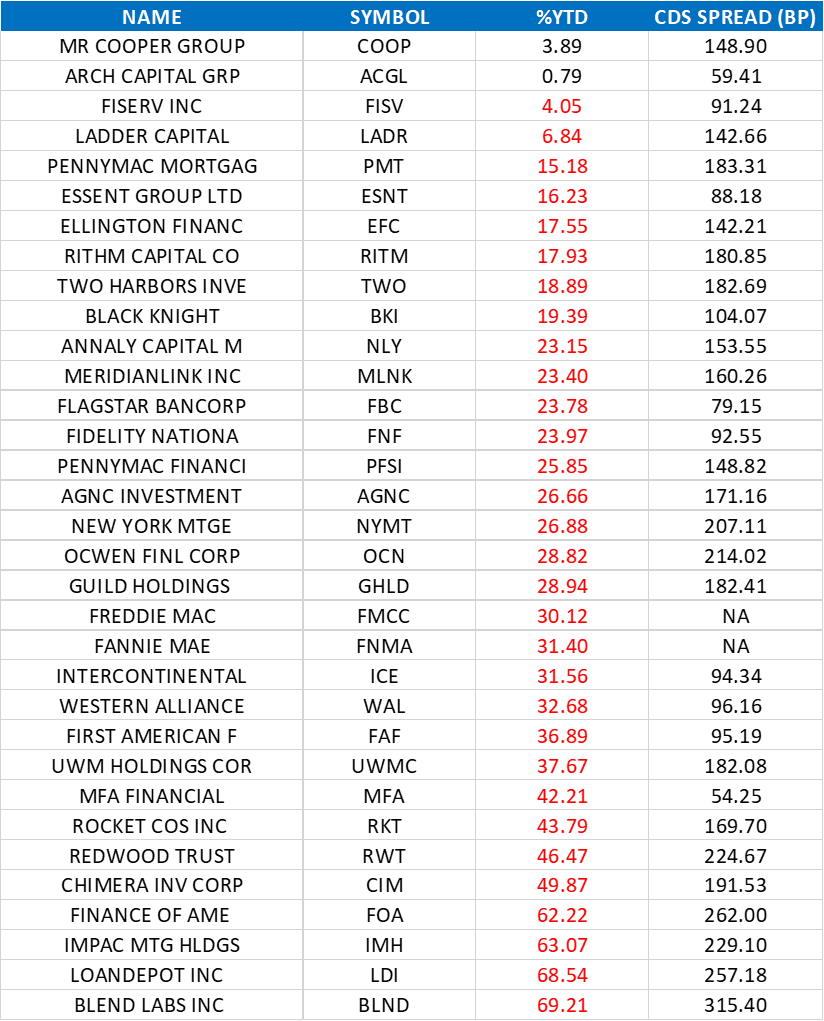

The nightmare scenario now approaching in the government loan market is that FHA loan delinquency rises into the teens and the resultant drop in cash flows from performing loans force servicers to advance cash until they reach the point of insolvency. Without the flow of profits and liquidity from new loans, government seller/servicers are basically consuming capital until the FOMC drops interest rates. And the McCargo Rule at Ginnie Mae may accelerate the outflow of cash from government seller/servicers and so make a systemic event in the government loan market more likely in 2023. Our mortgage equity surveillance group is shown below:

Source: Bloomberg

We expect to see the firms with larger servicing portfolios perform well in this difficult environment, in part because the low prepayment rates and high cash flows from these portfolios will serve as a source of support in 2023 and beyond with volumes less than half of 2020-21 levels. But more important, the government seller servicers with proficiency in buying MSRs and recapturing prepayments will find a ready source of liquidity with the larger banks.

Like the larger independent mortgage banks (IMBs), the traditional providers of warehouse financing such as JPMorgan (JPM) and Flagstar (FBC) are seeing a thinning out of the competition as volumes fall and recent arrivals head for the exits. A number of large regional and foreign banks that jumped into warehouse and MSR lending last year are going to be leaving the sector in short order. And most significant, Wells Fargo (WFC) is exiting 1-4s in terms of correspondent lending and warehouse.

Another significant development in the market is the restructuring of Credit Suisse (CS) and its investment bank, including the possible shutdown or sale of the bank’s structured products group. Bloomberg reports that the group, which has been involved in a number of MSR financing transactions, has been looking for outside capital. In another transaction, Select Portfolio Servicing Inc. (SPS) has struck a deal to acquire certain assets of Texas-based Rushmore Loan Management Services LLC, reports Housing Wire.

One leading government lender has gone from $20 billion in warehouse capacity this time last year to just $6 billion today, a stark illustration of plummeting industry lending volumes. In coming months, however, the demand for advance lines for delinquent and forbearance loans is likely to grow, presenting a real danger to the industry as opposed to the false alarm in 2020. Whereas the threatened liquidity crisis in 2020 was saved by the massive liquidity from the FOMC, today the Fed is out of the market and JPM and other major banks are net sellers of 1-4 family loans and MSRs.

We expect to see many smaller IMBs with smaller servicing portfolios forced to sell and/or close their doors over the next 12-18 months. While some of the larger public companies in our surveillance group have debt yields in the teens and credit default swaps (CDS) spreads above 200bp, the fact is that mortgage companies generally pay double digit rates for equity capital. The application of a couple of turns of leverage to the business of making and servicing 1-4s can be quite lucrative and far lower risk than a bank or broker dealer.

But more to the point, the IMBs that are likely to survive in the government loan market are going to be those firms that understand not only the value of the MSR in terms of periodic cash flow, but the more important optionality of the potential to refinance loans in the portfolio. Unlike investment assets that can move with a phone call, loan servicers that own MSR have the proverbial cake and get to eat it too. They control the asset but also control the optionality of a refinance event, which can represent several years’ worth of servicing income.

The firms in the government loan market that will be able to deal with a surge in loan delinquency will be those firms that will retain the support of the larger warehouse lender banks, even when running at a net operating loss. The banks will lend not because the IMBs have a certain amount of capital or because of the low credit risk of government assets. The large warehouse banks will lend because they understand that the value of the owned MSR, including the unrecognized value of the refinance option, is well in excess of fair value assigned to the MSR under GAAP and is thus the most important capital asset owned by an IMB.

The Institutional Risk Analyst is published by Whalen Global Advisors LLC and is provided for general informational purposes only and is not intended for trading purposes or financial advice. By making use of The Institutional Risk Analyst web site and content, the recipient thereof acknowledges and agrees to our copyright and the matters set forth below in this disclaimer. Whalen Global Advisors LLC makes no representation or warranty (express or implied) regarding the adequacy, accuracy or completeness of any information in The Institutional Risk Analyst. Information contained herein is obtained from public and private sources deemed reliable. Any analysis or statements contained in The Institutional Risk Analyst are preliminary and are not intended to be complete, and such information is qualified in its entirety. Any opinions or estimates contained in The Institutional Risk Analyst represent the judgment of Whalen Global Advisors LLC at this time, and is subject to change without notice. The Institutional Risk Analyst is not an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any securities or instruments named or described herein. The Institutional Risk Analyst is not intended to provide, and must not be relied on for, accounting, legal, regulatory, tax, business, financial or related advice or investment recommendations. Whalen Global Advisors LLC is not acting as fiduciary or advisor with respect to the information contained herein. You must consult with your own advisors as to the legal, regulatory, tax, business, financial, investment and other aspects of the subjects addressed in The Institutional Risk Analyst. Interested parties are advised to contact Whalen Global Advisors LLC for more information.

.png)

Comments