Macro-Prudential Delusions: Bank Credit Outlook 2H 2017

- May 29, 2017

- 10 min read

Updated: Feb 16

May 29, 2017 | In the mid 2000s, just before the financial crisis began, US banks were reporting credit metrics for all asset classes in loan portfolios that were quite literally too good to be true. And they were. The cost of bad credit decisions was hidden, for a time, by rising asset prices.

The same aggressive, low-rate environment used by the Fed to artificially stoke growth in the early 2000s has been repeated in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, only to a greater extreme. Today US banks report credit metrics in many loan categories that are not merely too good, but are entirely anomalous. Negative default rates, for example, are a red flag.

A decade ago, the more aggressive lenders such as Wachovia, Countrywide and Washington Mutual were actually reporting negative net default rates, suggesting that extending credit had no cost – in large part because the value of the collateral behind the loans was rising. In those heady days of comfortable collective delusions, non-current rates for 1-4 family loans were below 1%, the lowest levels of delinquency since the early 1990s.

This situation changed rather dramatically by 2007, when several large west-coast non-bank mortgage lenders collapsed. By the start of 2008, funding for banks, non-banks and even the GSEs was drying up and default rates were rising rapidly. The cost of credit reappeared. Net-charge off rates for 1-4 family loans in particular went from 0.06% early in 2005 to 1.5% by the end of 2008 and peaked at 2.5% by the end of 2009.

Today the irrational exuberance of the Federal Open Market Committee has created huge asset price bubbles in sectors such as residential and commercial real estate. A combination of low rates, a dearth of home builders (down 40% from ~ 550k firms in 2008 to ~ 330k firms today) and even less construction & development (C&D) lending (down ~ 30-40%) has constrained the supply of homes. But low rates sent prices for existing homes soaring multiples of annual GDP growth – both for single-family and multifamily properties.

Keep in mind that the folks on the Federal Reserve Board think that asset price inflation is helpful – thus the “wealth effect.” Specifically, the FOMC believes that manipulating risk preferences, credit spreads and therefore asset prices helps the economy to generate more income and employment. Many analysts have debunked the notion of a “wealth effect,” but the FOMC persists in this thinking even today. Mohamed E-Erian writing in Bloomberg has it right:

“Forced to use the 'asset channel' as the main vehicle for pursuing its macroeconomic growth and inflation objectives – that is, boosting asset prices to make consumers feel wealthier and spend more, and also to increase corporate investments by fueling animal spirits – the Fed has ended up providing exceptional multiyear support to financial markets using an experimental array of unconventional tools and forward policy guidance. Indeed, most investors and traders are now conditioned to expect soothing words from central bankers – and, if needed, policy actions – the minute markets hit a rough patch, virtually regardless of the reason.”

In an economic sense, the Federal Open Market Committee is the heart of the Administrative State. The use of the “asset channel” to pretend to boost economic activity is part of the larger delusion at the Fed known as “macro-prudential” policy. The macro-prudential worldview sees the Fed as an all knowing, all-seeing global managerial agency that can somehow balance goosing economic growth using asset bubbles with preventing the associated systemic risks. Note that regulating whole industries and constraining growth is, in fact, a key part of the Fed’s macropru model.

Having maintained low interest rates and used trillions of dollars of bank reserves to fund open market purchases of Treasury bonds and agency mortgage paper, the FOMC now faces an asset market that has understated the cost of credit for over a decade. From 2001 through 2007, and then 2009 through today, the FOMC has boosted asset prices – but without a commensurate and necessary increase in income. The Fed has, to paraphrase El-Erian, decoupled prices from fundamentals and distorted asset allocation in markets and the economy.

SO the question that concerns The IRA is when will the credit cycle turn and how much of the apparently benign credit picture we see today is a function of the Fed’s social engineering? If this latest round of Fed “ease” is more radical than that seen in the early 2000s, will we see an even sharper uptick in bank loan loss rates than we saw in 2007-2009?

Total Loans

Let’s start with the big picture perspectives of all US banks using our favorite chart, which juxtaposes pre-tax income with provisions for credit losses in the chart below. Note that quarterly pre-tax income for all US banks has slowly crawled back over $60 billion, resulting in net income in the low $40 billion range. The industry’s average tax rate was just below 30% on the $18.8 billion in taxes paid in Q1 2017.

Source: FDIC

Looking next at the $9.3 trillion in total loans for all US banks, the picture in the chart below is relatively calm. Note that the rate of non-current loans at 1.3% is still elevated above pre-crisis levels as are net loan charge-offs. Also, particularly note that in 2009 all non-current loans spiked to over 5%, yet net-losses after recoveries (loss given default or “LGD”) peaked at just 3%.

Source: FDIC

Loss given default at 75% is near the historic lows seen in 2006 and previously in the early 1990s. Think of LGD as the inverse measure of recoveries since the quality of the collateral behind the bank’s loan is the key determinant. Industry LGD for all bank loans fell to a low of 70% in 2014 when the bubble in residential and commercial real estate was roaring. Rising LGD for all bank loans today suggests that the bloom is off the rose in bank loan portfolios.

Source: FDIC

1-4 Family Loans

The $2.4 trillion in loans secured by 1-4 family residential properties is actually smaller in absolute terms and as a percentage of the bank balance sheet than it was a decade ago. In Q1 2000, loans secured by 1-4 family homes were 32% of total bank loans, but today that same metric is just 25% of total loans. Keep in mind that bank balance sheets have more than doubled since 2000 from $4.3 trillion in total loans to $9.3 trillion today. How’s that for an inflation indicator?

Sales of residential mortgages in the agency and government market are also down sharply for all US banks, reflecting a secular migration by banks away from 1-4 family mortgage loans as the asset class of choice for American banks. Compliance risks and high operating expenses make the residential mortgage sector among the lowest return on equity asset classes.

With non-current rates still at 3% vs 1% for the decade before the 2008 crisis, the credit quality of bank portfolio loans does not seem to have improved looking at the numbers. Net charge-offs at 0.4% are back down at pre-crisis levels. Looking at the chart below, loan losses seem to have been suppressed for almost two decades starting in the early 1990s.

Source: FDIC

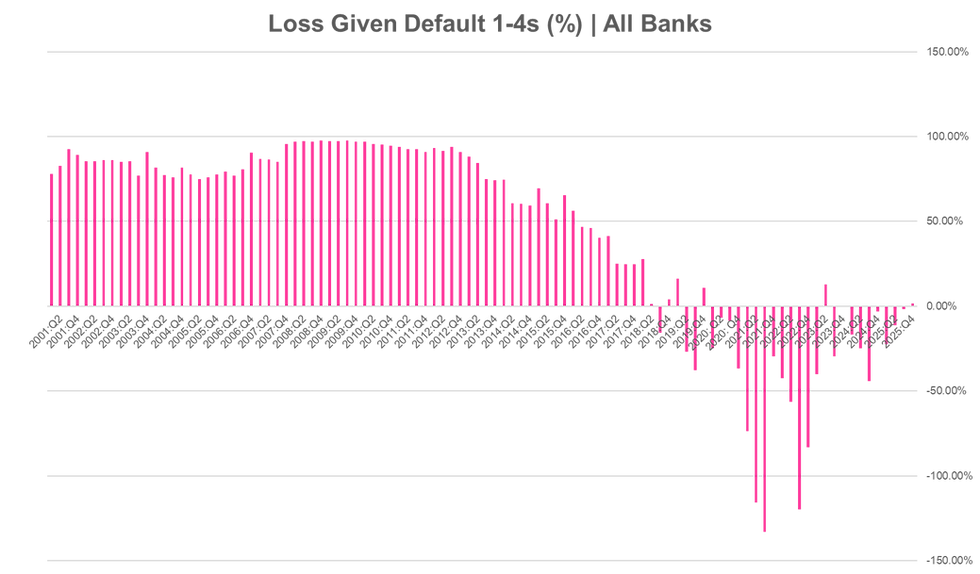

More interesting, however, is the sharp, falling off the cliff movement of LGD for 1-4 family mortgages. Since the 2008-2010 period when LGDs were near 100% of the total unpaid principal balance, today loss given default for the average bank portfolio home loan is just 40% and lower than at any time since 1990. The chart below really shows the effect on credit performance of the Fed-engineered increase in asset prices since the financial crisis. But when do we revert to the mean?

Source: FDIC

So while the percentage of 1-4 family mortgage loans past due remains high, LGD is at all time lows. Go figure. Again, the principal driver of low loss rates seems to be the double digit home price appreciation since 2012.

Credit Cards

Another asset class that has been very popular with investors and the financial press of late is bank credit cards. The industry’s $750 billion in total portfolio credit card loans has seen non-current and default rates rising. The chart below shows noncurrent loans vs. charge-offs. Unlike other loan categories, notice that charge-offs of bad credit card debts are above the rate for noncurrent loans.

Source: FDIC

Capital One (NYSE:COF) warned last quarter on future defaults. COF saw net charge-off rates rise 42 bps year over year to 2.50% compared to the industry average of 3.6%, a statistic that suggests there are some far riskier books in the industry besides just-below-prime operations such as COF.

Further, COF reported that provision for credit losses surged 30% from the year-ago quarter to $1.99 billion. Sadly the FDIC does not release publicly the data on provisions for future losses by loan type, an important piece of information that would enrich the public record.

The chart below shows LGD for the credit card portfolio of all US banks. Notice this is a pretty stable metric for loss net of recoveries that fluctuates between 80-90% of the loan amount.

Source: FDIC

“During the first quarter, banks charged-off $11.5 billion in loans, an increase of $1.4 billion (13.4 percent) over the total for first quarter 2016,” notes the FDIC’s Quarterly Banking Profile. “This is the sixth consecutive quarter that charge-offs have posted a year-over-year increase. Most of the increase consisted of higher losses on loans to individuals. Net charge-offs of credit card balances were up $1.3 billion (22.1 percent), while auto loan charge-offs increased $199 million (27.7 percent), and charge-offs of other loans to individuals rose by $474 million (66.4 percent).”

C&D Loans

Today the world of real estate construction lending is very different than before the 2008 financial crisis. A decade ago, much of the C&D book was focused on single-family homes. Today banks focus on commercial and multifamily properties. The latter category has tended to be rock solid in the major metro areas, even through the 2008 crisis.

From 2008 to 2010, about 1/3 of the ~ $600 billion C&D portfolio for all US banks was charged off, restructured or repaid. New lending dried up. This left a lasting caution on the part of regulators and the industry when it comes to lending on dirt. In the beginning of 2008, the total bank C&D portfolio in the US was $631 billion, but today it is just $390 billion.

In 2008, there was $180 billion in 1-4 family residential construction loans held by all FDIC insured banks, but today there is just $70 billion. When you consider the factors behind the lack of supply in single family homes in the US, start with the sharp reduction in credit for the construction sector. And recall that bank balance sheets have grown 20% since 2008, so the proportion of bank portfolios allocated to financing housing construction has also dropped sharply relative to other loan types.

Source: FDIC

But to really see the handiwork of the FOMC, you need only look at the loss given default for C&D loans. During the early 1990s and the 2008-2012 periods, note that LGD was nearly 100% of the loan amount. Banks in the Southeast and Southwest failed in droves as development loans were taken to the curb and then written off entirely.

But since 2012, the market manipulation of the Fed has caused LGDs on construction and development loans to go sharply negative, suggesting that this credit exposure has no risk or cost. In mathematical terms, recoveries on defaults are exceeding charge-offs by a wide margin, suggesting that asset prices for land and improvements are rising very rapidly. There may also be some resolutions of past defaults in the data -- going back five years or more.

Source: FDIC

So how does this all end? In the short term, look for default rates on consumer exposures to continue rising. But in asset classes like commercial real estate, residential homes and C&D lending, we suspect that the party may continue, at least in statistical terms, through at least the end of the year.

After that, however, we full expect to see loss rates and LGDs start to snap back to the middle of the proverbial distribution. As one well-placed bank CEO told The IRA over breakfast, “there are lots of sweaty palms” in the New York commercial real estate market. Read this little missive in The New York Times about the Park Lane Hotel to get a sense of the level of exuberance in the commercial real estate market in Gotham.

Without a rather robust confirmation of asset prices with rising incomes, as El-Erian and many others have observed, current levels of assets prices are unlikely to be maintained. In the event, look for bank default and recovery rates to normalize, with a sharp increase in credit costs for lenders and bond investors alike.

Trees do not grow to the sky, credit costs are never really negative, and last we looked, Fed chairs cannot fly through the air or spin straw into gold. But they can manipulate asset prices and cause other mischief that, we suspect, represents a net cost to consumers and investors alike. But this is hardly a novel state of affairs.

In that regard, we appreciate your comments about our earlier missive, “Buy Britain, Sell Europe.” Many of you challenged our idea that Britain is an enduring nation state, while the EU is merely a bad idea whose sell by date has passed.

To address these comments, we refer to one of our favorite reads of late, “Playing Catch Up,” by Wolfgang Streeck. The emeritus director of the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies in Cologne, Streeck writes regularly for the London Review of Books. He is ready to suspend democratic processes to support “willing governments” that advance German-style reforms, but Streeck has a cogent view of the European political economy:

“Here, as so often in her long career, Merkel is anything but dogmatic, and certainly isn’t beholden to ordoliberal orthodoxy since what is at stake is Germany’s most precious historical achievement, secure access to foreign markets at a low and stable exchange rate. For several years now, Berlin has allowed the European Central Bank under Draghi and the European Commission under Juncker to invent ever new ways of circumventing the Maastricht treaties, from financing government deficits to subsidising ailing banks. None of this has done anything to resolve the fundamental structural problems of the Eurozone. What it has done is what it was intended to do: buy time, from election to election, for European governments to carry out neoliberal reforms, and for Germany to enjoy yet another year of prosperity.”

Sound familiar? In the US as well as Europe, what passes for fiscal and monetary policy are merely a series of short-term expedients meant to get us from one day to the next. The nonsense of macro-prudential policy represents the apex of such thinking. As we look out to credit conditions in the US banking sector in 2H 2017 and beyond, the one sure bet is that the cost of credit will not remain suppressed forever.

.png)

Comments