Professor Edward Altman: Risk On

- Jul 1, 2018

- 5 min read

New York | Last week The Institutional Risk Analyst attended an evening presentation by Professor Edward Altman of NYU Stern School of Business at The Lotos Club of New York. Entitled “The Altman Z-Score After 50 Years: What is it Saying About Current Conditions & Outlook for Global Credit Markets,” Professor Altman’s comments were as usual understated and entirely on point.

“Fifty years ago, we published the Altman Z-Score,” Dr. Altman told the audience of friends, colleagues and former students. “Frankly I am as surprised as anyone that it is still around.” The five factor Z-Score model published by Dr. Altman in 1968 is shown below:

Dr. Altman attributes the longevity and, indeed, growing popularity of the Z-Score to the fact that the model is simple and easily replicated, and the fact that is works. “Empirical finance models generally have a half life of a couple of years…. But if the model is simple, easy to replicate – and replication is really important in scholarly finance – and is accurate, then other researchers start to compare their models to the simple model.”

“The other reason that the model is still around is that it is free,” Dr. Altman notes.

According to its founder, the Altman-Z Score has predicted roughly 80-90% of all non-financial bankruptcies since it was first published. The Z-Score is entirely public source and is used without commercial restriction in business, corporate finance and investing. Needless to say, the Z-Score and its derivatives generate a lot of traffic online at portals such as Bloomberg, Credit Risk Monitor and S&P.

“All I wanted was one penny [per hit],” Dr. Altman says of his elegant creation, which is “simple, accurate and free.” Invoking author Malcom Gladwell’s book “Outliers,” Altman says that his work would have been created by another researcher as computers became more wisely available in the 1960s. “It is really important to be in the right place at the right time,” he observed. This confirms our judgment in “Ford Men: From Inspiration to Enterprise that luck is the most important thing in life.

Dr. Altman witnessed the birth of the high yield or “junk” bond market in the early 1980s, a market that encompassed the world of sub-investment grade credits. “The market in 1982 was about $10 billion and comprised of fallen angels, companies that were beautiful at birth and investment grade, but like all of us as we get older we get ugly,” says Altman. “We lose our hair, we get wrinkles and we get downgraded.”

Since that time, the Z-Score has been incorporated in corporate and bank risk models for corporate default or “mortality” as Dr. Altman likes to say. In particular, the three zones of “safe,” “grey” and “distress” in terms of credit originally defined by Dr. Altman are now widely disseminated and accepted as benchmarks. He explains the evolution of the model and its use:

“The guidelines we established back in 1968 were the so-called zones. Above 2.99 the firm was in the safe zone. Below 1.8, in the distressed zone with a highly likely probability of bankruptcy. By the way, above 3.0 and below 1.8 the Z-Score had a 100% accuracy back in 1968. The model was built for manufacturing companies and in those days big companies did not go bankrupt. Things have changed. The zones are enshrined on the Internet, on Google and Wikipedia, but the problem is that they are no longer appropriate. But that doesn’t keep people from using it because its on the Internet and the Internet is always right.”

Dr. Altman explains that there has been an incredible migration of risk in the US economy over the past fifty years reflected in the increased debt leverage in the system. He notes that when the high yield debt market was born, the market was measured in single digit billions, but today the total junk debt outstanding is $3 trillion globally and more than half in the US. Likewise leveraged loans did not exist, but today this is a $1 trillion market that fuels much of the total non-investment grade debt issuance. Altman also believes that the fact of global competition and capital markets has led to more, larger bankruptcies.

“In a good year there are roughly 50 bankruptcies of companies with assets more than $1 billion, what we call billion dollar babies,” notes Altman. “As a scientist in this area, I love bankruptcies. Already this year, in this benign credit cycle, we’ve had 14 billion dollar bankruptcies.”

Altman states that as the amount of debt leverage has increased in the global economy there has been a compression of credit ratings: “How many 'AAA' rated companies in the US? Two. Johnson & Johnson and Microsoft. Two left. Why is it that there are not more 'AAA' rated companies? Leverage.”

The migration of companies down to “BBB” ratings simply reflects the fact of more debt and the desire to stay this side of the line of investment grade. “What rating would you like to be as the chief financial officer of a company,” ask Altman. “We did a survey many years ago and the answer was ‘A.’ What is it today? ‘BBB’ The ‘BBB’ category is exploding. That is the preferred rating. Why? Because if you are ‘A’ it means that you are not exploiting low cost debt. If you are ‘BBB,’ it means that you have higher effective returns for your shareholders. This is why over the past fifty years credit risk has migrated from very low to very high. It has exploded into a global debt bubble and this is not just companies. It's governments and households.”

Turning back to mortality, Altman spoke about how “life expectancy changes over the life of a person or a company – what we call contingent probability. In financial markets much like real life, promises are made to be broken. How do you break a promise? You default. You don’t pay back as promised. When assessing default probability, we’ve got gorgeous ‘AAA’s, handsome ‘AA’s, decent looking ‘BBB’s, not so good looking ‘BB’s, and downright disgusting ‘CCC’s. And people have been buying those disgusting ‘CCC’ bonds with great frequency over the past five years.”

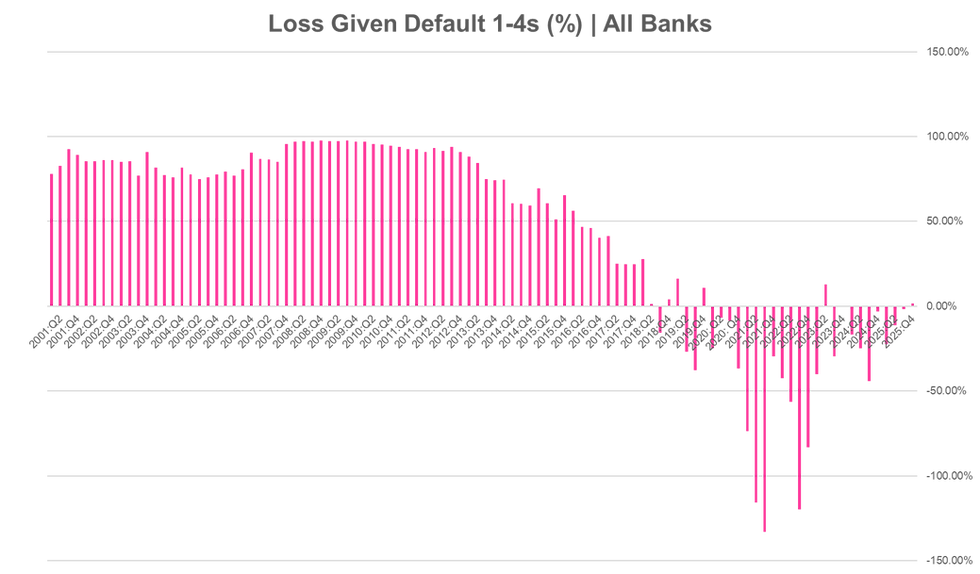

Dr Altman notes that “we are in a benign credit cycle” and that non-financial corporate debt levels vs. GDP are back to 2008 levels, yet default rates remain low – below 2%. Indeed, the Z-Scores for corporate issuers have risen from 4.8 in 2007 to 5.1 in 2017 even as debt levels have grown. He also notes that high recovery rates for bond and loan investors, plus low interest rates and credit spreads, and ample liquidity, are all signs of benign credit cycle “that has gone on, incredibly, for eight years.”

And yet Professor Altman is hardly sanguine about the immediate outlook. “We have been in a ‘risk on’ cycle, meaning easy money and brisk buying,” Altman observes. “Risk on means that people forget risk and take a lot more exposure to get higher yields in this low-rate environment. Using a baseball metaphor, we are in extra innings with respect to the benign credit cycle. Investment grade debt has been exploding since 2007 and high yield debt is also up. A lot of this money is being used for corporate stock buybacks.”

“Shrinking equity and exploding debt is a disaster waiting to happen – and it will happen if we have another recession,” Altman concludes. “And we will. Its just a matter of when. I’m not a forecaster of economic activity, but surely given the accumulation of debt, if we have a recession then we will have another credit crisis. It may not be as big as 2008, which was more focused on households. This time the risk is more in the corporate area. But unless things change in terms of market discipline, we are going to have some very nasty repercussions in the debt markets.”

.png)

Comments