Banks and the Fed's Duration Trap

- Nov 30, 2017

- 5 min read

Atlanta | Is a conundrum worse than a dilemma?

One of the more important and least discussed factors affecting the financial markets is how the policies of the Federal Open Market Committee have affected the dynamic between interest rates and asset prices. The Yellen Put, as we discussed in our last post for The Institutional Risk Analyst, has distorted asset prices in many different markets, but it has also changed how markets are behaving even as the FOMC attempts to normalize policy.

One of the largest asset classes impacted by “quantitative easing” is the world of housing finance. Both the $10 trillion of residential mortgages and the “too be announced” or TBA market for hedging future interest rate risk rank among the largest asset classes in the world after US Treasury debt. Normally, when interest rates start to rise, investors and lenders hedge their rate exposure to mortgages and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) by selling Treasury paper and fixed rate swaps, thereby pushing bond yields higher.

An essay on this very subject was published by Malz, Schaumburg et al in a blog post for the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in March 2014 (“Convexity Event Risks in a Rising Interest Rate Environment”). Since then, the size of the Fed’s portfolio has grown a bit, and volatility has dropped steadily. The key characteristic to note is that the Fed owns most of the recent vintage, lower coupon MBS that would normally be hedged by private investors and banks. For those of you who follow our work, this argument tracks that of our colleague Alan Boyce, who has long warned about the hidden duration risk in the bond market since the start of QE. The FRBNY post summarizes the situation nicely:

“When interest rates increase, the price of an MBS tends to fall at an increasing rate and much faster than a comparable Treasury security due to duration extension, a feature known as the negative convexity of MBS. Managing the interest rate risk exposure of MBS relative to Treasury securities requires dynamic hedging to maintain a desired exposure of the position to movements in yields, as the duration of the MBS changes with changes in the yield curve. This practice is known as duration hedging. The amount and required frequency of hedging depends on the degree of convexity of the MBS, the volatility of rates, and investors’ objectives and risk tolerances.”

Since the Fed and other sovereign holders of MBS do not hedge their positions against duration risk, the selling pressure that would normally push up yields on mortgage paper and longer-dated Treasury bonds has been muted. Thus the Treasury yield curve is flattening as the FOMC pushes short-term rates higher because longer-dated Treasury paper, interest rate swaps or TBA contracts are not being sold, either in terms of cash sales by the FOMC or hedging activity. Chart 1 shows 2s to 10s in the Treasury bond market from FRED.

Source: FRED

More, the volatility normally associated with a rising interest rate environment has also been constrained because the Fed’s $4 trillion plus portfolio of Treasuries and MBS is entirely passive. As the FOMC ends purchases of Treasuries and MBS, and indeed begin to sell down the portfolio, presumably the need to hedge by private investors and financial institutions will push long-term rates up and with it volatility. As Malz notes, “the biggest change [between 2005 and 2013] is the increase in Federal Reserve holdings, partly offset by a large reduction in the actively hedged GSE portfolio.” Yet since the modest selloff in 2013, volatility in the Treasury market has continued to fall.

While it is clear that some smart people at the FRBNY understand the duration dilemma, it is not clear that the Fed staff in Washington and particularly the members of the Board of Governors get the joke. Unless you believe that the FOMC is intentionally pursuing a flat yield curve as a matter of policy, it seems reasonable to assume that the folks in Washington do not understand that reducing the size of the System portfolio is a necessary condition for normalizing the price of credit.

George Selgin at Cato Institute wrote an important post this week talking about Chair Janet Yellen’s defense of paying interest on excess reserves (IOER) held by banks at the Fed (“Yellen's Defense of Interest on Reserves”). Selgin’s analysis raises a couple of important issues.

The fact that Yellen and the FOMC will not manage IOER at or below the market rate for Fed Funds is quite telling, particularly since doing so would address many of the key criticisms of the policy. This suggests two things, first that there really is no "free" trading in Fed Funds anyway and the Fed is the market. Second that the FOMC somehow thinks that it must push higher the bottom of the band -- this despite the huge net short duration position of the street and the $4 trillion passive Fed portfolio.

The more urgent question is Yellen's view of a trade off between QE/open market operations and IOER that Selgin illustrates very nicely. The FOMC seems to think that merely not growing the portfolio or slowly selling is an option while they raise benchmark rates like IOER and Fed Funds. In fact, reducing the portfolio always was the first task, before changing benchmark rates. Especially if one is cognizant of current market conditions.

Unless the FOMC changes its approach to managing its $4 trillion securities portfolio, either through outright sales or active hedging, it seems likely that the Treasury yield curve will invert by Q1 ’18. The Fed could sell the entire system portfolio and the street would probably still be short duration due to low rates and continued QE purchases by ECB, BOJ, etc. And to repeat once again, the agency mortgage securities market is down 30% on issuance YOY. Again, the FOMC does not seem to appreciate that the yield curve must invert, unless the bond trading desk at the FRBNY is actively selling and/or hedging all of the MBS and even longer dated Treasury paper.

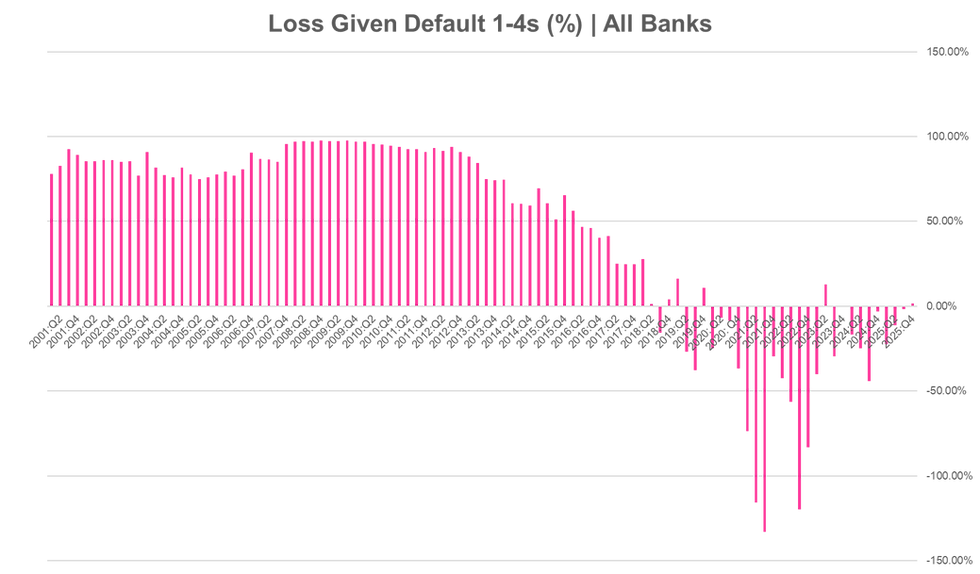

Some analysts such as Ed Hyman (Barron’s, “A Smooth Exit Seen for Mortgage Securities,” 11/20/17) believe that banks will increase purchases of agency paper as the Fed unwinds QE. We beg to differ. Bank holdings of MBS as a percentage of total assets has barely moved in years. But more to the point, one has to wonder if Yellen and other members of the FOMC appreciate the trap that has been created for holders of late vintage MBS.

The Fed has suppressed both interest rates and volatility via QE, as shown in Chart 2 below:

Source: Bloomberg

As and when the balance between buyers and sellers in the MBS market slips into net supply, volatility will explode on the upside and the considerable duration extension risk hidden inside current coupon Fannie, Freddie and Ginnie Mae MBS could prove problematic for the banking industry.

“The duration extension risk goes turbo if we see rates up, volatility up and a curve steepening,” notes Boyce. Or as Malz noted succinctly in 2014:

“When interest rates increase, the price of an MBS tends to fall at an increasing rate and much faster than a comparable Treasury security due to duration extension, a feature known as the negative convexity of MBS. Managing the interest rate risk exposure of MBS relative to Treasury securities requires dynamic hedging to maintain a desired exposure of the position to movements in yields, as the duration of the MBS changes with changes in the yield curve. This practice is known as duration hedging. The amount and required frequency of hedging depends on the degree of convexity of the MBS, the volatility of rates, and investors’ objectives and risk tolerances.”

.png)

Comments