For Powell, it's the Agony of the Convexity

- Mar 15, 2020

- 6 min read

“It is not learning, grace nor gear

Nor easy meat nor drink

But bitter pinch of pain and fear

That makes creation think”

They Told Barron: The Notes

of Clarence W. Barron (1930)

New York | Just how low is the lower bound in US mortgage rates? We may have found out over the past few months. The benchmark 10-year Treasury bond fell to almost zero this past couple weeks, but the companion 30-year mortgage has actually gone up in yield.

Now with the Fed dropping the target for fed funds to zero and restarting quantitative easing, will mortgage rates comply with the Fed's guidance? Our bet is maybe. But why are mortgage rates not falling? One word: convexity. When a mortgage bond goes down in price when everything else is rising, that is called convexity. To quote “Fabozzi Bond Markets and Strategies Sixth Edition,”

“The key point is that measures (such as yield, duration, or convexity) reveal little about performance over some investment horizon because performance depends on the magnitude of the change in yields and how the yield curve shifts. Therefore, when a manager wants to position a portfolio based on expectations as to how the yield curve is expected to shift, it is essential to perform total return analysis.”

We are seeing one of those rare events, like a lunar eclipse, where unseen market forces actually thwart the intentions of central bankers and the hopes of a lot of mortgage lenders. We hear many complaints from the secondary mortgage channel about rising primary rates. Now the Federal Open Market Committee has overtly resumed quantitative easing and again includes mortgage backed securities on the shopping list. But will mortgage rates fall below 3%?

The Chart of the Week from March 6th posted by the Mortgage Bankers Association tells the convexity story with the rising spread between the 10-year Treasury note and the 30-year mortgage.

Today the federal funds rate is a government managed number. Are mortgage bonds next in terms of explicit government manipulation? Probably too big a lift, even for the Fed. What does this say about the efficacy of monetary policy and, in particular, the choice by the FOMC several decades ago to target the overnight rate for federal funds as its monetary tool of choice?

Prior to WWI, the benchmarks for the fixed income were high grade corporate bonds and even the bonds issued by Great Britain and other European nations. Government finance was barely considered. Indeed, prior to the creation of the Fed in 1913, where the Treasury deposited its cash balances was the big question on the minds of financiers. But in the 1980s, the FOMC began using the rate for overnight lending between banks as its benchmark for policy.

For decades, the FOMC could drop the target for fed funds and the housing market would respond. But now that relationship is in doubt. The private markets for debt and equity in the US remain quite large and provide an effective check on Fed efforts at outright manipulation of markets. Witness the housing market.

The nearly $12 trillion in outstanding mortgage debt in the US is the result of originating a couple trillion annually in new mortgages. The average 30-year mortgage actually prepays within 8-10 years, at least in theory. These loans are originated by brokers, financed by large finance companies, banks and REITs, and ultimately sold to investors in the global bond markets.

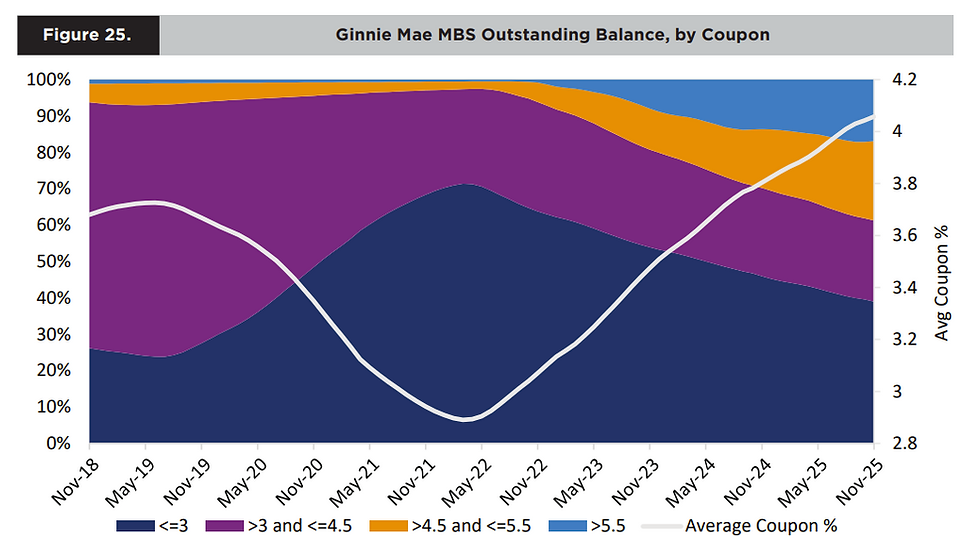

About half the market is conventional mortgages guaranteed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, a bit more than 20% resides in government insured loans that are financed via Ginnie Mae securities, and the rest is held directly in portfolio by commercial banks.

The second largest market in the world is the forward or “TBA” market in mortgage securities. Because of the assumed 8 to 10-year average life of a residential mortgage, the markets tend to price these assets against the 10-year Treasury. But in fact, thanks to the extreme volatility of interest rates, the agency and government RMBS markets have seen prepayments accelerate, thereby making the effective life of these securities more like 4-5 years.

Markets try to value agency RMBS against the 10-year Treasury, but in fact the 5-year Treasury note is probably a better bet. Yet in either event, the spread between government bond yields has widened in recent months, directly challenging the Fed’s continued use of federal funds as the benchmark for policy. The chart below shows the 10-year Treasury bond and the 30-year fixed mortgage average from Freddie Mac.

Much like the Vatican in Rome, the Federal Reserve Board is reluctant to make changes to canon law. First among these rules is the idea that the Fed can effectively execute monetary policy through the few large banks – aka “primary dealers” – that directly face the Fed as counterparties. Second, the Fed’s changes in policy, once transmitted via the primary dealers, will influence the US economy and particularly housing finance and related sectors such as home building.

The dealer-centric world of the FOMC not only creates liquidity problems for markets but now seems less and less effective in terms of influencing housing. Since housing broadly defined is one of the biggest parts of the US economy, whether the FOMC can use interest rate targets to influence credit availability in housing is kind of a big deal. But we also need to raise another issue in this regard and that is the growing inventories of unsold Treasury debt on the books of large, primary dealer banks.

With a nod to our friend Marshall Auerbach at Levy Economics Institute, we hereby rehabilitate the long discredited economic notion of “crowding out.” The combination of liquidity and capital rules for big banks, crazy levels of volatility, and massive Treasury issuance of new securities has sapped the Street’s ability to efficiently finance debt – all debt. Add to this the natural reluctance of investment managers to lose money and we have today’s situation: massive liquidity coming to the dealers from the FOMC, but ebbing liquidity in the rest of the global money markets.

While the yield on the US Treasury 10-year bond came close to the zero bound last week, the forward market for mortgages rates actually backed up in yield, further widening the secondary market spread. Investors suspect that prepayments will accelerate, thus they discount the premium coupons still left in the market and yields rise. New production GNMA 3s are being priced around 3.5X cash flow multiple, according to SitusAMC.

We have it on good authority from several large mortgage issuers in New Jersey that a GNMA 2% coupon was briefly quoted offscreen in the TBA market last week, but by the close on Friday, GNMA 2.5s were the lowest coupon offered in TBA. With the Fed's rate action and QE resumed, will the housing market’s response to the latest Fed action remain muted? Look for GNMA 2s to reappear on dealer TBA screens next week, but will they actually trade in significant volumes? Only if mortgage rates fall.

The Fed has the ability to influence markets, but the private debt and equity markets in the US are still too large for the FOMC to overtly manipulate. Should the FOMC decide, in its arrogance, to buy existing 3.5% and 4% coupons in RMBS in an effort to force mortgage interest rates down, the Committee should not be surprised that they will take significant losses due to prepayments. The FOMC also may find itself the among a dwindling number of buyers of agency and government RMBS if 30-year mortgage rates actually go below 3% annual rates and RMBS coupons fall accordingly.

For now, at least, there remains a limit on the ability of the central bank to intimidate private investors into taking losses on mortgage securities. The way out of this monetary cul-de-sac is for the FOMC to gradually shift away from explicit targeting of the federal funds rate and towards a regime focused on the legal mandates of employment and prices, two relevant yet fuzzy concepts that provide better political cover for the Fed.

The downside risk of sticking with the current regime is considerable. With the disappearance of LIBOR, for one thing, federal funds and the TBA market becomes the de facto benchmark for private finance in the US. Does the FOMC propose to manage the federal funds and TBA markets after LIBOR actually disappears? Imagine how different market conditions might be if the FOMC ceased providing guidance on federal funds entirely and simply provided the volume of liquidity necessary to clear the markets?

To us, continuing to beat the proverbial dead horse by targeting federal funds seems only to be creating excess volatility in the markets and little else in terms of public policy. For one thing, without the Fed’s clumsy effort to manage fed funds higher in 2018, the level of prepayments in the world of residential mortgages would be a good bit lower. We suspect also that the level of volatility in the global equity markets would be less as well.

And Chairman Jay Powell and other FOMC members could take themselves out of the media crosshairs. Ending the FOMC’s targeting of fed funds might be a big win for all concerned. See below our comments to Barron’s last week as carried by Fox Business.

.png)

Comments