The Interview: Michael Bright of SFIG

- May 16, 2019

- 6 min read

New York | In this issue of The Institutional Risk Analyst, we speak to Michael Bright, President and CEO of the Structured Finance Industry Group (SFIG). Prior to joining SFIG, Michael was the EVP and Chief Operating Officer of the Government National Mortgage Association, or Ginnie Mae. As COO he managed all operations for Ginnie Mae’s $2.0 trillion portfolio of mortgage-backed securities. Before joining Ginnie Mae, Michael was a director at the Milken Institute’s Center for Financial Markets. In 2013 Michael was a principal staff author of S.1217, the "Corker-Warner" GSE reform bill that passed the Senate Banking Committee the following year. While in the office of U.S. Senator Bob Corker, he also advised on a range of Senate Banking Committee regulatory policy issues.

The IRA: Michael, let’s start off by talking about the early part of January 2019 when you departed from Ginnie Mae to join SFIG. The markets had just been through a very tough month. A lot of securities issuance essentially went to zero. Mortgage securities had been in a slump since that September. Fortunately the markets have largely bounced back, particularly corporates and mortgages. How do you think about that period and since then as head of SFIG?

Bright: I have not had a lot of folks asking about the drop off in issuance. There were a lot of factors that combined to make December a challenging month for many of our members, including the Fed reducing the size of its balance sheet and the general increase in interest rates at the end of last year. And when it comes to mortgages, there are a lot of households out there with three and four handle mortgages, so there is a limit on how much production volume that you will see even given a decline in rates. Our job at SFIG is to facilitate and coordinate the dialog about just these issues among all of the participants in structured finance.

The IRA: How would you describe the mood of the structured finance community in 2019? What sort of risks or issues are top of mind for your members?

Bright: I’d say the mood is cautious optimism. Default rates are low and the overall tenor of the markets is quite positive, but the thing that makes all of us take pause is the question of how long can the current cycle last? How long can interest rates stay where they are or even move lower? The narrative has changed a lot since last year, so the biggest anxiety for issuers and the professionals that advise them is really uncertainty as to the market trend and how much of a role will the Fed play in the future. We are conditioned to expect extremes in market movements, so the prolonged period of relative calm is hard for people to process one way or another because there is no clear trend in credit or interest rates.

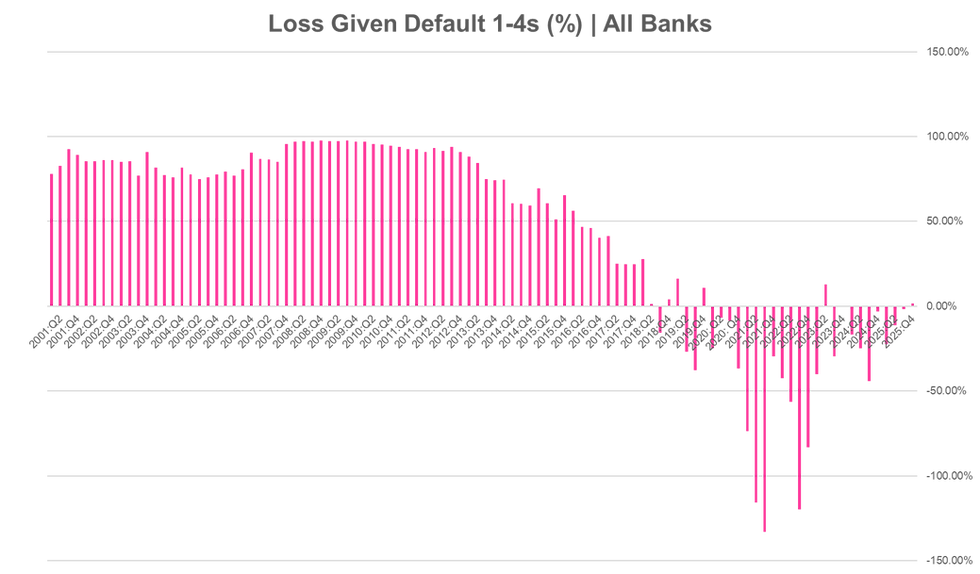

The IRA: The financial media is constantly trying to hype every market move into some sort of cataclysmic event, but we don’t actually see that in the credit markets. Credit is benign and volatility is low. Net default rates on bank 1-4s, multifamily and even construction exposures are negative, suggesting that credit has no cost. We saw this phenomenon with a few banks in the 2000s, but now its the whole sector.

Bright: I think you have two issues at work here. The media is endlessly searching for the "canary in the coal mine" story, the big expose that will reveal some unknown risk. Yet at the same time, you have a financial industry that is now so well capitalized and so risk averse that at times it seems hard to imagine how we could repeat the experiences of 2008. So the media continues to pursue a narrative that says catastrophe is around the corner, but we don’t see that as an industry and we do push back against that doom and gloom narrative.

The IRA: One topic that is getting a lot of attention from policymakers in Washington is leveraged loans. Congress is holding hearings on the topic and presidential aspirants such as Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) have made it part of their campaign spiel. There is even some novel litigation now about whether the 1930s era securities fraud laws should apply to leveraged loans. Do you see a problem in this market in terms of risk?

Bright: If you trace the history of the Fed’s quantitative easing or QE, the growth of leveraged loans tracks the Fed’s intentions to take risk free assets out of the system and force investors into riskier products. At first the worry over QE was that it would stoke inflation, but none of those concerns materialized. Around 2013 and 2014, the discussion moved to whether manipulating risk preferences would result in unintended consequences in terms of financial instability. And the Fed did not even disagree. They conceded that financial instability could be a consequence of QE. Both Chairman Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen were asked that specific question in their congressional testimony. The response from the Fed was that financial instability is a risk but we’d rather deal with deflation now and then deal with any financial stability problems later. Loans have been made to riskier companies and this is precisely what the Fed said five years ago that they wanted to see. So there is no surprise here. The default rates on leveraged credit are still very low, and it may go higher in the future, but nobody wants to be the one who misses the next big risk.

The IRA: Well Chairman Jay Powell says that asset prices are not inflated, but you could make the case that the Fed wanted to inflate asset prices to counter the deflationary tendency cause by the massive accumulation of debt in the system. Given the relatively tranquil credit environment that we’ve discussed, what is on top of your agenda at SFIG?

Bright: Our agenda at SFIG is to foster a dialog between the structured finance industry and policy makers. We have a unique position in the US because we have a structured finance market that allows lenders to create secured assets, finance this production and eventually sell those assets to end investors. This is an incredibly valuable asset for the people of the United States and has a big role to play in fostering and sustaining economic growth. But with the benefits of structured finance also come responsibilities. People in our industry know that getting it wrong on risk has real world consequences that can endanger financial institutions, markets and the entire economic equation. Educating policy makers about the benefits and potential risk is our job at SFIG.

The IRA: The arbitrage in the financial markets post 2008 has been to move into asset classes that were not center stage in the last crisis. Commercial real estate, leveraged loans, collateralized debt obligations, auto loans have all grown significantly over the past decade. Issuers of leveraged loans, for example, have taken the position that the securities fraud laws from the 1930s don’t apply to these assets and therefore all bets are off when it comes to protecting investors. Do you worry that this sort of regulatory arbitrage may conceal risks that are significant to the industry and policy makers both?

Bright: As an organization, SFIG has both the issuers and the investors under the same tent, so we are very focused on enabling precisely the sort of discussion that helps our community understand these issues and any attendant risks. We don’t just advocate for issuers. There is an important ongoing conversation between investors and issuers on topics such as loan covenants and other protections. One of the great things about my job is that our chief goal is to bring all of our members together to discuss these issues on a continuing basis. Do we worry about these issues? Of course, that is our job.

The IRA: Going back to your days at Ginnie Mae, one of the big questions on the table is what happens to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac once they exit federal conservatorship. The new head of the Federal Housing Finance Administration, Mark Calabria, has said that the GSEs need more capital to exit conservatorship. There are people in Washington who seem to believe that the GSEs can operate as they do today without a federal credit wrapper. Do you worry about what happens to the mortgage market if the political sound bite about “protecting taxpayers” becomes an end of credit support for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac?

Bright: There are two outcomes for the GSEs that are unambiguously safe for the financial markets. The first is conservatorship. The markets understand conservatorship and accept that the Treasury is backing both GSEs. Ginnie Mae paper trades at a slight premium to the GSEs, but they are close enough. The market also understands a congressionally authorized credit wrapper as is the case with Ginnie Mae explicitly. Those are the two extremes that the markets understands. This is why foreign central banks are comfortable with Ginnie Mae because the governmental wrap is clear and unambiguous. The middle ground is quite unclear in terms of market acceptance. The idea that there is some amount of private capital that gets you to the same market acceptance as either conservatorship or an explicit guarantee from Treasury strikes me as wishful thinking. Any outcome that does not involve explicit credit support for the GSEs runs the risk that markets and particularly global investors will not accept it.

The IRA: Thanks for your time Michael

.png)

Comments