Housing Finance in 2018

- Dec 19, 2017

- 6 min read

To read our post in The American Conservative on the growing bitcoin fraud, see the link at the end of this issue. Happy holidays!

The US housing market is completing another year of rising home prices in many – but not all – parts of the country. We’ve been in a sellers market for single family homes since 2012, fueled first by low prices, then by low interest rates, then lower FHA premiums, and also the relative dearth of new home construction. So with interest rates slowly normalizing and significant changes to the tax code, what does the future hold in store for housing finance?

For the past eight years, the FOMC has been boosting housing with low interest rates and purchases of MBS. More, for the past half century, public policy in the US has encouraged home ownership with a variety of subsidies and tax breaks. Now, however, Congress is turning the thrust of public policy away from encouraging home ownership in a way that could have serious negative implications for an important part of the US economy. Chart 1 below shows the Case-Shiller home price index since 2007.

As the tax legislation takes effect, a number of observers are predicting that high-cost markets on the east and west coasts could see prices fall by double digits – this despite the continued squeeze on supply. Over the longer term, notes Jonathan Miller of Miller Samuel, the loss of deductions for state taxes and mortgage interest will put downward pressure on prices in high cost markets. Think Scarsdale NY. Elimination of mortgage deductions for second homes and home equity lines also will negatively impact affluent destination markets around the US.

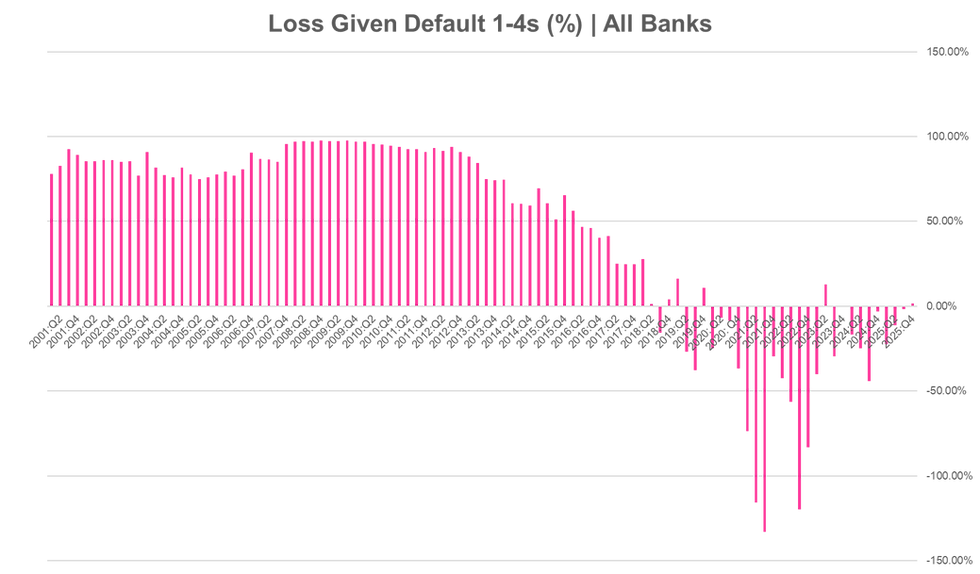

The impending tax reform legislation in Washington could not only mark a significant change in the price dynamic for home prices, but it may also signal a negative credit trend for investors in 1-4 family mortgages. As households are forced to pay out more cash for federal taxes and mortgage payments, there will be less remaining cash flow in these households overall. Price compression will also affect perceived wealth and also aspirational pricing. But the big question is how the tax bill will impact overall volumes for home purchases and new mortgages.

The latest data from The Mortgage Bankers Association shown in Chart 2 shows a slight uptick in mortgage lending volumes for Q3 and Q4 2017, a welcome bit of good news for the industry after the single-digit profitability seen in the first half. Even today, lending profitability spreads are running a tad under a quarter of 2007 levels, putting intense pressure on non-bank lenders especially.

Source: MBA

The good news is that the MBA estimates show total mortgage debt volumes growing 10% to $11 trillion by 2019, this due to expectations of rising interest rates and lengthening durations on mortgage-backed securities (MBS). Purchase mortgages are expected to grow steadily while refinance transactions are flat-lined at around $100 billion per quarter in the MBA estimates.

More than a little of that increase in total mortgage debt, however, comes in the form of rising home prices and mortgage balances. Of the 1.7 million loans originated in Q4 2016, the average of the $461 billion in originations was about $275,000 per loan. Of note, the average size of purchases mortgages is now around $310,000 vs $260,000 for a mortgage refinancing, as shown in Chart 3.

Source: MBA

The big question near-term is whether all of the talk about higher interest rates will actually result in higher yields for the benchmark 10-year Treasury bond. In the wake of the latest rate hike by the Federal Open Market Committee, spreads actually tightened. We continue to believe that the size of central bank portfolios globally means low volatility and no significant selling pressure on long-dated government debt in 2018.

Even if the FOMC were to take our advice and start selling MBS outright, we don’t believe that long rates would rise very much if at all. As we noted last week in our conversation with Bob Eisenbeis of Cumberland Advisors, the FOMC is more worried about losing money on the Fed’s portfolio than it is about the impact of QE on the bond markets. The result will be a flat yield curve and spread compression for leveraged investors such as banks and REITs. But the forward Treasury issuance calendar suggests at least some upward pressure on rates in the medium terms, as mortgage finance maven Rob Chrisman opines:

“Foreign central banks that use Treasuries to manage currency exchange rates are not facing the market forces that would require a return to the amount of accumulation seen over the last decade. As a result, the private domestic and foreign sectors would be left as a principle buyer of Treasuries. Baring another financial crisis, it is unlikely that a significant increase in demand for safe-haven assets is on the horizon. If demand for Treasury debt does not keep up with the expected increase in supply, yields will need to rise.”

We think that the supply/demand scenario in US Treasury bonds becomes an issue, ironically, when the Fed accelerates its planned asset reduction and thereby allows volatility and volume to return to the trading markets. The FOMC ought to be concerned with restoring something like normal function in the bond markets after years of induced monetary coma, even if it means taking a loss on the system portfolio.

It will be interesting to see how Chairman Powell deals with this sticky political issue of losses on the Fed’s huge securities book, particularly in an environment where the FOMC continues to raise short-term rates. Historically, the 10-year Treasury has floated about 2% above inflation, but as Jim Glassman at JPMorgan ("JPM") noted in June: “The slump in Treasury yields is almost entirely due to quantitative easing distorting the ‘real’ component of interest rates.” Ditto.

The FOMC currently has Fed funds targeted at 1.5% and hopes to move this benchmark rate to 2.75% over the next couple of years. With statistical measures of inflation still at or below the 2% target for prices, this suggests a 10-year bond closer to 3% than to 4% -- at least in normal circumstances. But with global central banks still sitting on $20 trillion in securities and still buying, market conditions are hardly normal.

Central bank positions in US Treasury and MBS suppress both volatility and trading volumes, reducing upward pressure on long-term yields. We believe that one of the better trades for 2018 may be a long position in the 10-year Treasury with a short on the 2-year Treasury note!

Looking at estimates from the MBA and other economic estimates, the consensus seems to have the Fed funds rate hitting 2 ½% by 2019 and the 10-year over 3%. We wonder, however, if the continued purchases by the ECB and Bank of Japan, and the go-slow policy of crawling normalization adopted by the Fed, won’t keep an effective cap on long-term interest rates. We see the possibility of a rally in the 10-year in 2018 with tighter spreads and an inverted yield curve, a turnabout that could have an interesting impact on housing finance.

The tight spread regime engineered by the Fed and other central banks has negatively impacted all manner of consumer lenders, with effective loan pricing near all-time lows. Large banks fight for jumbo prime mortgages at pricing that makes no sense – but they simply want the assets. The same pricing logic governs credit spreads in auto paper or commercial real estate and other types of business lending.

The fact that most of the major investment banks have guided down, again, on trading revenues reflects the fact that QE and low rates have sucked the life out of the private financial markets. With most global asset classes still largely correlated, predicting what happens out beyond 2019 becomes real guesswork. Until the Fed and other central banks agree to stop accumulating securities, the private markets measured by volatility or volume or trading profits will suffer accordingly. How is this helpful?

Final thought on housing. One other impact of the tax reform legislation is that the reduction in corporate tax rates will cause a proportional reduction in the value of tax loss assets to shelter future revenue. Citigroup ("C") will reportedly write-down $16 billion alone, but will still have plenty of accumulated losses to shelter income for years to come. And the erstwhile GSEs, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, will likewise need to write down capital to reduce the value of tax loss assets.

In the event, both GSEs are likely to need additional capital draws from the US Treasury. We wonder if the Trump Administration will use the fact of the additional advances to the GSEs as a legal pretext to put both of the entities into receivership. Without new legislation, the only way to end the conservatorship of the GSEs is to put them through a formal receivership process.

While for many in the housing industry restructuring the GSEs is truly thinking the unthinkable to borrow the title of Herman Kahn’s classic book, “On Thermonuclear War”, receivership has been discussed as a policy option at the White House and would be supported by many Republicans.

In the event President Donald Trump decides that housing finance may provide some political leverage, all of the comfortable assumptions about mortgage production or credit spreads or even interest rates will fall by the wayside. Next year is an election year, after all, and tax cuts and reforming the GSEs makes for good conservative political fodder.

The American Conservative

.png)

Comments