Sizing the Commercial Real Estate Bust

- Jun 7, 2020

- 9 min read

Updated: Jun 9, 2020

"You pass the Helmsley Palace, the shell of old New York transparently veiling the hideous erection of a real estate baron..."

Jay MacInerney

Bright Lights, Big City (1984)

New York | So how big is the impending commercial real estate bust in the US? Bigger than the residential mortgage bust of the 2000s and also bigger than the commercial real estate wipeout of the 1990s, including the aftermath of the Texas oil boom of the late 1970s and 1980s.

Commercial real estate as a mortgage asset class is half the size of the $11.5 trillion market for residential homes, but the losses this cycle could be far larger per dollar of assets. That’s big. Both markets are fundamentally affected by interest rates above all.

The US has not experienced a really nasty deflation in commercial real estate prices since the 1990s and, before that, the bust in the Texas oil patch in the late-1970s. Abby Livingston told the story of Houston during the oil bust in The Texas Tribune last month (“All of the party was over": How the last oil bust changed Texas”):

“Real estate soon emerged as the most noteworthy outlet for Texas money. With growth in commerce and in population, it seemed quite logical at the time to invest big in new housing developments, soaring skyscrapers in Dallas and Houston, shopping centers, and vacation condominiums on South Padre Island.”

Last week, the Financial Times reported that Chesapeake Energy Corporation (NYSE:CHK), the pioneer of shale oil created by Aubrey McClendon, is on the brink of bankruptcy. This not only signals the end of the US oil boom, but another surge in real estate speculation in the areas affected. From the New York border southwest along the Appalachian Mountains to Texas and as far west as California, shale exploration and production financed a period of giddy real estate investment that is now suddenly ended.

Equity REITs own more than $2 trillion of physical real estate assets in the U.S. including more than 200,000 properties in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, NAREIT reports. The equity REITs, as the name suggests, are generally funded with equity rather than debt, but individual assets are routinely encumbered with mortgages to increase returns.

The latest Mortgage Bankers Association survey shows that commercial banks continue to hold the largest share (39 percent) of commercial/multifamily mortgages at $1.4 trillion. Agency and GSE portfolios and MBS are the second largest holders of commercial/multifamily mortgages, at $744 billion (20 percent of the total). Life insurance companies hold $561 billion (15 percent), and CMBS, CDO and other ABS issues hold $504 billion (14 percent). The chart below shows the equity REITs and the various classes of commercial mortgage lenders and investors.

Source: NAREIT, MBA, FDIC

This particular bust in commercial property is very different from the 1990s, but in common with that era also includes a large energy component. The difference is that, due to COVID19 and the more recent looting in major cities, the valuation of once solid urban commercial and residential properties held by equity REITs is now very in much question.

The fact of the COVID19 lockdown, the riots and looting following the killing of George Floyd by the Minneapolis Police, and the coincident rise of telecommuting, which keeps people away from the large metros, raises questions about the entire economic structure of cities. So long as social distancing is required or even the preferred option, many of the institutions and structures within the big cities no longer function.

Connor Dougherty and Peter Eavis reported in The New York Times on Friday:

"Faced with plunging sales that have already led to tens of millions of layoffs, companies are trying to renegotiate their office and retail leases — and in some cases refusing to pay — in hopes of lowering their overhead and surviving the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. This has given rise to fierce negotiations with building owners, who are trying to hold the line on rents for fear that rising vacancies and falling revenues could threaten their own survival."

And the operative term is survival. Add the Shale oil bust to the already precarious state of the commercial real estate market in major metros and the image becomes truly catastrophic. In 1981, oil peaked at $31.77 per barrel, at the time an unheard-of valuation for black gold. The FDIC tells the tale in their excellent History of the Eighties:

“The bottom hit in 1986. Oil was priced at $12.51, still high compared with 15 years before. But historical context was no help to oil producers who plunged deep into debt buying up rigs amid the frenzy to meet anticipated demand. The economic angel of death for oilmen came in the form of bankers calling in loans.”

The 1980s were a tough time in Texas as politicians and business leaders were forced to liquidate business and their personal possessions to pay debts. Much like the shale oil industry today, the domestic oil industry was forced to adjust to changes in oil prices that made these assets uneconomic. But the wider speculative bubble in commercial real estate reached all around the nation. The FDIC continues:

“When the bust did arrive in the late 1980s and continued into the early 1990s, the banking industry recorded heavy losses, many banks failed, and the bank insurance fund suffered accordingly. Compounding the magnitude of these losses was the fact that many banking organizations active in real estate lending had weakened their underwriting standards on commercial loan contracts during the 1980s.” Sound familiar?

Source: FDIC

The troubles in the oil patch were only part of the economic disaster of the 1980s and early 1990s. The collapse of the residential mortgage market and the S&L industry put home prices into a deep freeze for much of a decade. But the 1980s were also a very difficult time for commercial real estate and a number of major US cities, which had been abandoned by affluent households fleeing the violence and chaos of the inner cities.

After a catastrophic fiscal crisis in New York during the 1970s, followed by the famous blackout and rampant acts of arson, the cities saw mass abandonment of commercial properties, leaving many inner cities derelict. The famous 1977 New York City blackout and subsequent riots destroyed parts of the city and saw public services cut to the bone.

Whereas the nadir of the riots and burning of 1977 in New York marked a starting point for the rebirth of the city decades later, today New York City stands on the edge of the abyss.

Changes in social behavior threaten decades of real estate investments in the highest cost market in the US. Yet the overtly left media led by The New York Times, the impending collapse of the urban economy in New York is cause for celebration.

What is similar to the 1990s and before was the role of the Federal Open Market Committee in encouraging the financial excesses in commercial lending as part of a broader policy of asset reflation. In the 1970s and 1980s, banks piled into a new asset class known as real estate is a desperate effort to offset losses on loans to Third World nations.

Then Fed Chairman Paul Volcker refused to allow US banks to write down bad loans to Argentina and other debtor nations until he left office in August 1987, but the workout of bad commercial loans continued for years to come. The Fed’s aggressive reflation strategy in the 1980s worked, only too well, causing the banks to inflate a vast bubble in commercial real estate that deflated through the 1990s.

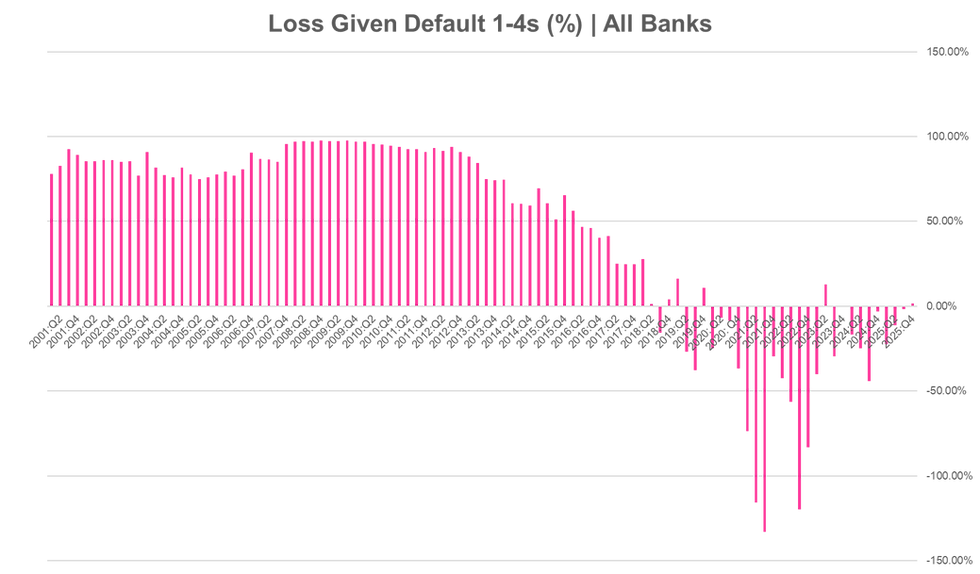

Since 2008, low or zero interest rates have again caused an even bigger bubble in commercial real estate assets, a gold rush that drove net loss rates negative as loan-to-value ratios plummeted. Now with asset prices in a free fall, LTVs are rising and we expect to see net loss rates on commercial exposures solidly in the red this quarter. Get used to it.

Source: FDIC/WGA LLC

The Scope of the Damage

The state of the equity REITs casts a pall over the rest of the $5.2 trillion commercial mortgage segment. Once seen as top commercial credits, these equity REITs now face an enormous change in how businesses and consumers view urban commercial office and multifamily residential assets. As usage falls, so too do valuations and tax revenues for the localities.

Projects that a year ago might have made sense as long-term bets on the future of cities like New York have no economic rationale today. And the loans and mortgage bonds that support these buildings no longer make any financial sense. Ponder all of the commercial buildings in New York and other major metros that depend upon tourism, hospitality and entertainment for their economic life. Without these features, there is no reason to be in these metro areas.

The cardinal rule of landlords is that the most important thing is to be aware of your tenants, their needs and their financial situation. When your tenants just get up and leave, however, defaulting on leases and filing bankruptcy, the economic model for rental buildings and condominiums falls apart.

Part of the difficulty of estimating loss rates for commercial properties is that every property is different, every loan is different, sometimes in very significant ways. Whereas you can generalize about residential assets at the portfolio level, with commercial loans the analysis is asset-by-asset, loan-by-loan.

Commercial real estate brokerage CBRE says hopefully that “The real estate recovery will lag the economic recovery, with multifamily and industrial recovering first, followed by office and retail.” But the reality at the loan levels suggests otherwise.

Consider an example: “WFCM 2013-LC12” or the Wells Fargo Commercial Mortgage Trust, a CMBS issued in 2013 with a combination of hotel and retail use commercial properties. Back in 2017, Fitch Ratings noted that the deal “has exhibited relatively stable performance since issuance” and reaffirmed the ratings. But things change.

More recently, Kroll Bond Ratings downgraded several tranches of the CMBS because of likely losses from the foreclosure of Rimrock Mall, among other factors. KBRA writes:

“As of the May 2020 remittance period, there are two REO assets (1.3%) and one loan in foreclosure (0.4%). In addition, there are 16 loans (24.9%) that appear on the master servicer's watchlist, including four loans (2.1%) that are 30 days delinquent. The REO assets, the loan in foreclosure, 10 watchlist loans (11.6%), and three other loans (13.6%) have been identified as KBRA Loans of Concern (K-LOCs). K-LOCs consist of specially serviced and REO assets as well as non-specially serviced loans in default or at heightened risk of default in the near term.”

KBRA continues: “Excluding K-LOCs with losses, the transaction’s weighted average (WA) KBRA Loan-to-Value (KLTV) of 91.6% has increased from 87.7% at last review and decreased from 99.2% at securitization. The KBRA Debt Service Coverage (KDSC) of 1.67x has decreased from 1.76x at last review and 1.69x at securitization."

So, the good loans, excluding the likely losses and doubtful assets, have an LTV over 90%. The equity in many of the remaining properties may already be gone depending upon the location and utilization levels. Bank owned CRE, by comparison, tend to have initial LTVs closer to 50, but those assets may also have seen significant erosion in the equity and thus an increase in effective LTV.

And by no coincidence, the prices for WFCM 2013-LC12 have suffered since the start of 2020. The most junior D tranche of this CMBS was trading in the mid-90s after the start of the year, but then suffered several downgrades and resultant drops in price.

Today the Ds trade below 70 or about 1,600bp over the curve. If you are lucky enough to hold the bonds, you get the idea. The As are flopping around below par or plus 180bp over the curve after touching 98 in mid-March.

So how big will the commercial real estate bust be in 2020-21 and beyond? In 1991, the FDIC reports, “the proportion of commercial real estate loans that were nonperforming or foreclosed stood at 8.2 percent, and in the following year net charge-offs for commercial real estate loans peaked at 2.1 percent.”

In 1991, the net charge off rate for all $1.6 trillion in bank owned real estate loans was less than 0.5% Multifamily mortgage loans peaked in Q4 of 1991 around 1.5% of net charge offs but remained elevated until 1996.

But this time is different. Based on our informal survey of REIT valuations and individual assets, we think that the world has been turned upside down for many investors. Actual LTVs for urban commercial and luxury residential assets in many metros are well-over 100 and are likely to be restructured, albeit over a period of years. As we noted last week, it's all about buying time.

We think that net charge offs on commercial loans could rise to 2-3x the peaks of the 1990s, with loss rates at 100% percent or more in some cases, and remain elevated for years to come as the workout process proceeds.

Failing some miraculous economic rebound in the major metros, look for credit costs related to commercial real estate to climb for REITs, CMBS investors, the GSEs, and banks in that order of severity. Figure a 10% loss spread across $5 trillion in AUM over five years?

If you have questions about a specific situation, please contact us at info@rcwhalen.com

.png)

Comments