Powell Missteps on Corporate Bond Purchases

- Jun 18, 2020

- 6 min read

New York | Jay Powell made his first major misstep as Federal Reserve Board Chairman by allowing the central bank to start buying corporate debt. Using the canard of following an index of investment grade debt to guide the purchases does not make the error any less egregious. Buying the existing debt of an issuer is unlikely to change investor perceptions or the effective cost of capital, and creates risk for the Fed.

While buying Treasury bonds and mortgage back securities has a broad effect on the markets and credit spreads, purchases of corporate debt is a very focused subsidy with little promise of helping the economy or the specific issuers. Whether we talk of the Fed buying ETFs or corporate bonds, what is the policy justification of this activity?

As our friend David Kotok at Cumberland Advisors reminded us last night, "fishing is not catching." Indeed, since we are likely to see record bond issuance in Q2 2020, we think it is appropriate to ask what the FOMC thinks it is achieving? Note the chart below from FRED shows corporate credit debt spreads back to the early 1990s. Looking at 2008 vs today, what's the problem Chairman Powell??

Last week our friend Frank Partnoy published a prescient piece in The Atlantic (“The Looming Bank Collapse”). This article caused some considerable consternation in Washington, particularly among members of the Financial Stability Oversight Counsel. A recognized expert in asset backed securities who teaches law at UC Berkley, Partnoy boldly predicted the failures of large banks due to accumulating defaults inside collateralized debt obligations or “CLOs,” the latest flavor of poison distilled by the major Wall Street firms.

Partnoy argues with considerable authority that impending defaults of sub-investment grade debt (aka “crap”) that typically comprises CLOs will be so widespread that investors will lose money even on the “AAA” rated tranches of these deals. Banks hold a great deal of direct and indirect exposure to this supposedly “high investment grade” rated debt. Partnoy writes:

“It is a distasteful fact that the present situation is so dire in part because the banks fell right back into bad behavior after the last crash—taking too many risks, hiding debt in complex instruments and off-balance-sheet entities, and generally exploiting loopholes in laws intended to rein in their greed. Sparing them for a second time this century will be that much harder.”

Wall Street reacted to the Partnoy article by pointing out that CLOs performed quite well a decade ago and that current default rates are low. One bank research department prominently opined: “Currently, the U.S. CLO market is roughly $700 billion; U.S. bank CLO holdings are roughly $115 billion. Per public filings, roughly 80% of U.S. bank CLO exposure is held by 3 large banks, representing 1-2% of each respective bank’s total assets.”

But of course, this time it’s different. We recall similar arguments made about collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) a decade ago. Then the crisis was about crap securities based upon residential mortgages. This time around, the proverbial surprise is hidden in the world of corporate debt and related commercial real estate exposures. Ralph Delguidice of Pavilion Global Markets reminds us of a little history:

"One reason leveraged loans performed relatively well in the 2008 cycle was the significantly higher level of investor protection in the deals, as banks usually retained the loans on balance sheet. As demand has surged, CLOs have come to comprise more than half of the $1.7 trillion syndicated loan market through 2019. However, this demand has driven a significant erosion in loan quality, as ‘Covenant-lite’ and ‘loan-only’ structures (with no debt beneath the deal) have proliferated widely since the end of the GFC."

We think the worst-case scenario painted by Portnoy is unlikely to occur, but it cannot be dismissed. When the FOMC has Black Rock (NYSE:BLK) buying corporate debt, what surprises remain?? The quality of the collateral under many CLOs is true crap, even compared to a decade ago. That's why Portnoy's complaint did indeed twist some sweat soaked nappies at the Fed and Treasury into a knot at the end of last week.

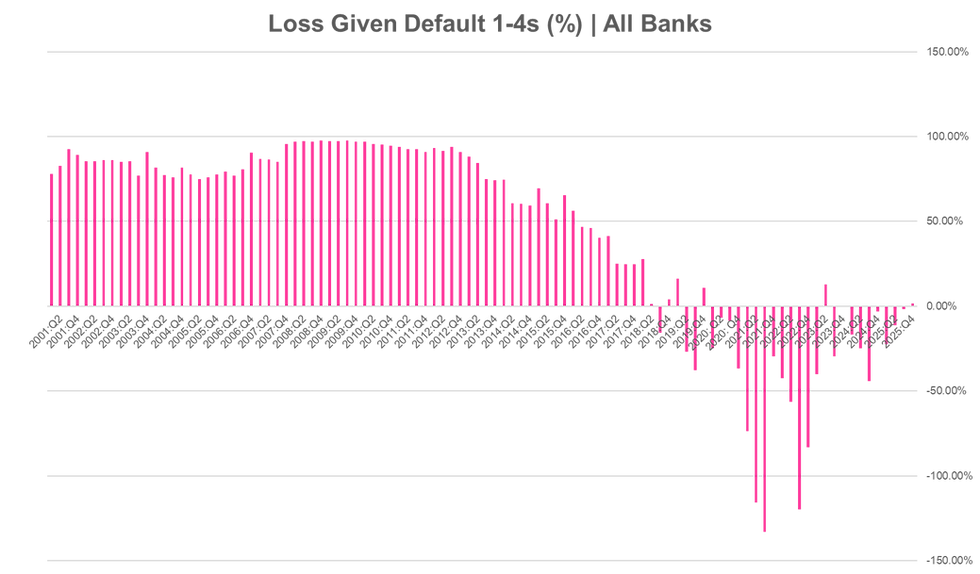

Corporate bond defaults in 2020 and beyond will be far worse than 2009. The Fed thinks that they need to “do something” in response, specially since they, like The Institutional Risk Analyst, know or at least suspect that we are in the early innings of a profound credit crisis. The chart below shows actual Q1 credit loss provisions for US banks and our updated estimate for Q2 2020.

Source: FDIC, WGA LLC

While bank loan default rates in most asset classes actually fell at the end of Q1 2020, net charge-offs for commercial and industrial loans doubled. Note that the polynomial trend line blasted through the two actual series for income and provisions, never a good sign when the future trend is down.

We expect credit costs to essentially consume all of bank operating income in Q2 and through 2020, making US bank earnings for the industry through the year likely to be a zero or less. We’ll be discussing the outlook for US banks further in the Q2 2020 edition of The IRA Bank Book, which will be released for sale to registered users of The Institutional Risk Analyst on Monday.

Sadly, however, the FOMC and the Federal Reserve System are uniquely ill-equipped to deal with problems of solvency as opposed to liquidity. While the Treasury and Federal Reserve have taken on a good deal of principal risk through the Main Street lending program, we view these extensions of credit more as grants than loans. Our pal Nom de Plumber outlines the situation very nicely from his vantage point inside the risk engine of Wall Street:

“In a Main Street loan, the private lender holds the IO (interest-only strip) while the Fed (taxpayers, once you pull away the velvet curtain) is the holder of the PO (principal-only strip) with all of the attendant risk. Net of origination fees, the private lender will have essentially only ~ 4% of the loan amount at stake initially. The lender is permitted to charge a 1% origination fee and also gets 25 basis points annually as a servicing fee. The Fed bears practically all the net economic exposure of the Main Street program, especially in terms of extension risk and default loss risk. Meanwhile, the lender collects fees over time, realizing that it retains little or no net principal downside upon any eventual default loss.”

As the Fed slips more and more into a de facto fiscal role a la the European Central Bank or even the Bank of China, the positioning of its actions grows ever more tenuous. Appearing before the Senate Banking Committee to deliver the Fed’s perfunctory semi-annual report to Congress, Powell said the Fed is not increases purchases through its an emergency lending program that, to date, has bought only exchange-traded funds.

“We’re not actually increasing the dollar volume of things we’re buying,” he happily reported on Tuesday. “We’re just shifting away from ETFs to this other form of index.” Please.

But whether we are buying ETFs or corporate bonds, the question remains as to the efficacy of this policy choice by the FOMC. No amount of open market bond purchases can fix the credit problems of the underlying issuers. Indeed, if the Fed holds these positions for any length of time, the central bank is likely to take a financial loss and become a creditor in private bankruptcies. Bad optics.

Not only is the Fed's bond purchase program of questionable utility, but it creates political risk for Chairman Powell and the Federal Reserve System. As we’ll discuss in our next issue, the real risk facing the financial markets and the US economy is that credit spreads are narrowing and equity market valuations measured by P/E ratios are rising, but earnings are falling and expenses are rising fast.

Question from Ralph: Can the arbitrage that created CLOs in the first place survive? If not, then Wall Street has a hole in earnings that will rival the hole caused by credit losses. At the moment, the decline of net operating income is due to rapidly rising credit expenses. But by the end of 2020, however, we expect to see earnings declines caused by a lack of new business volumes on and off Wall Street. That is, a decline in revenue even as credit costs remain elevated. Buckle up kiddies.

.png)

Comments