Wesbury: Repo Madness

- Sep 19, 2019

- 4 min read

In this issue of The Institutional Risk Analyst, we republish a commentary by Brian Wesbury, Chief Economist at First Trust Advisors, regarding the role of bank regulations in causing the liquidity squeeze in short term markets earlier this week. When Fed Chairman Jerome Powell says there is no connection between market tightness and monetary policy, he is right. The culprit is bank regulations that restrict the ability of banks to provide liquidity to the markets, as we wrote yesterday in Zero Hedge.

In the past few days, stresses in the financial system have shown up. These stresses have pushed the federal funds rate above the Federal Reserve's desired target range of between 2.00% and 2.25% (as of Tuesday), and some reports have funds trading as high as 9%.

The Fed has responded by using repos - re-purchase agreements - to put cash into the system and bring down short term interest rates. The question is, does this signal a systemic problem in the banking system. Our answer: an emphatic NO.

We believe the stresses are caused by overzealous banking regulation put into place after the crisis of 2008. The most likely culprit being LCR, or the liquidity coverage ratio.

Below is a quote from Jamie Dimon, CEO of JP Morgan, during a panel discussion at a Barclays financial services conference on September 10th, 2019.

"And I just want to mention. One way to look at the LCR thing and this, I'm talking about monetary transmission policy, you see recently China changed the reserve requirement. And when they do that, it frees up $100 billion of lending. You can't do that here because of LCR. Because – it's got nothing to do with monetary policies, it's a conflicting regulatory policy. And LCR also means that I can't finance a corporate bond and include it in liquidity anywhere. So when you all – if you all are selling corporate bonds one day, and you want JPMorgan to take on – finance $1 billion, I can't, because it'll just immediately affect these ratios. So we've taken liquidity out of certain products. And it won't hurt you very much in good times. Watch out when times get bad and people are getting stressed a little bit."

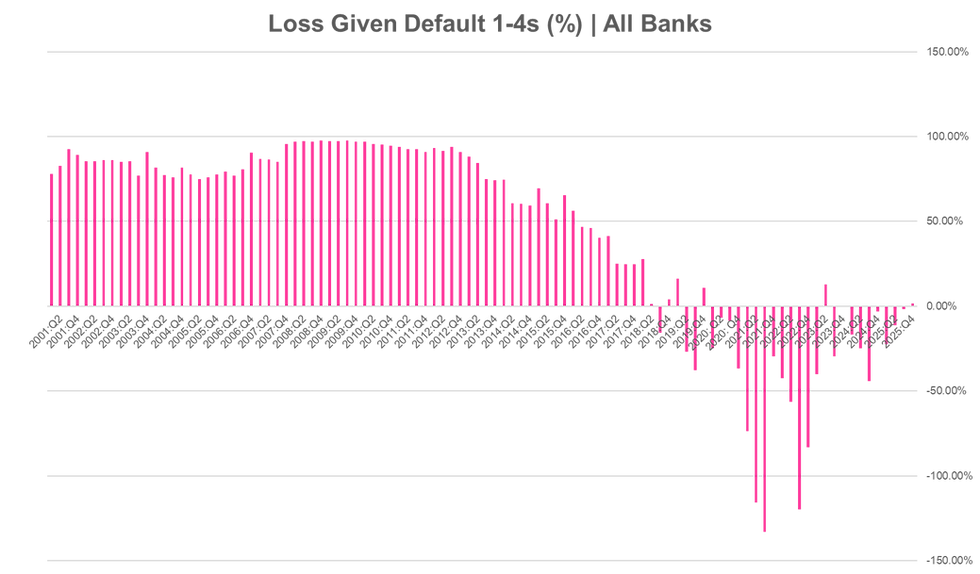

The LCR is calculated by bank regulators, and determines the amount of cash a bank would need in the event of a severe financial crisis. In other words, banks are forced to hold enough liquid assets to meet cash flow needs under a made-up stress test. These regulator-created stress tests are extraordinary, as are their estimates of potential losses.

So, how does this fit into today's financial market conditions and the management of monetary policy?

With the advent of quantitative easing, the Federal Reserve has put a massive amount of excess reserves in the banking system. However, the Fed has also limited banks' ability to use those reserves through regulation, by putting rules, like LCR, in place.

Stories about what that is going on with the repo market are filled with suggestions that the banking system does not have enough reserves. With $1.4 trillion of excess reserves in the US banking system, that's simply not true.

Because of those excess reserves, trading in the federal funds market has become very thin. Back in the 1990s, daily trading in federal funds was on the order of $150 to $250 billion per day and it climbed much higher in the 2000s. On Monday, total trading in reserves was just $46 billion, and in the past year trading in federal funds run near a 40-year low.

Why? Because banks are forced to hold more reserves than they actually need. QE flooded the system. A spike in the federal funds rate might have signaled a systemic (system wide) problem pre-2008, but not anymore.

So, what has happened this week? While the Fed isn't talking, this is our belief.

1) Fed rate cuts and low long-term rates increased the demand for mortgages, which reduced cash in banks.

2) Many companies also took advantage of lower rates and issued corporate debt, which some banks likely bought.

3) Oil prices spiked after the drone attack in Saudi Arabia and may have squeezed financial entities who had written contracts protecting their oil clients from changes in oil prices.

4) Third quarter corporate tax payments reduced deposits at US banks.

With such a small amount of federal funds trading, its highly likely that one or two (at most a small handful) US banks got caught offsides. We believe this is a short-term problem, not a long-term one.

One way to deal with this temporary issue is to change the overly strict rules on LCR and avoid limiting liquidity. That's our preference. It could also just let the market run and teach a small group of banks a lesson. Using repos or adding more QE is micro-managing the situation, it's not in the long-term best interest of the economy. Excess liquidity and rewarding bad management creates problems down the road.

But most important, these problems signal that the new path of monetary policy the Fed started in 2008 has grave issues. The Fed should not be as active in managing the economy as it has become.

In the end we think the market, and market pundits, have over-reacted. There are no true liquidity issues in the US, other than those caused by misguided regulation.

.png)

Comments